Reimagining the Royal and Vice-Regal Flags of the Commonwealth

Originally published in the Vexilloid Tabloid, no. 65,

Since the publication of this article, Queen Elizabeth II has been succeeded by King Charles III, and Barbados has abolished its monarchy. The substance of the proposal, however, still holds good.

Queen Elizabeth II reigns as monarch of 16 sovereign and independent countries. Although they share the same person as queen, each country’s throne is legally distinct: she is simultaneously and separately Queen of the United Kingdom, Queen of Australia, Queen of St. Lucia, etc.

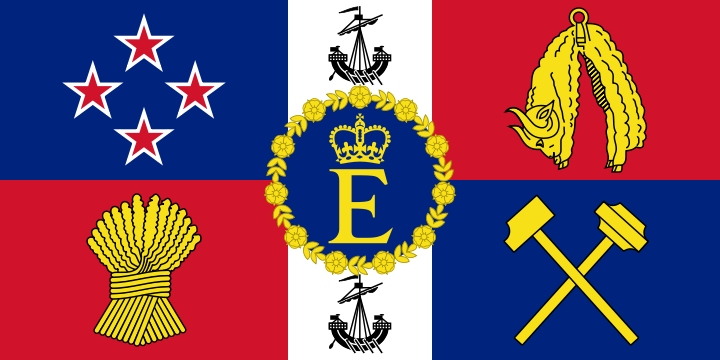

Some of these countries have adopted royal standards for the monarch’s personal use: usually a banner of the national coat of arms, defaced with Elizabeth’s personal badge of a crowned “E” in a wreath of roses. The royal standard of New Zealand is a typical example.

Since the queen lives in the United Kingdom, in her other 15 realms she is represented by a Governor General, who fulfills the day-to-day functions of the head of state. Most of these viceroys fly nearly identical flags: blue, with the lion-and-crown crest from the British royal arms above a scroll bearing the country’s name.

From a heraldic and constitutional perspective, the symbolism is not very satisfying. The crowned-“E” badge serves as an armorial mark of difference, seemingly indicating that someone other than the actual bearer of the coat of arms is represented. But as monarch, the queen is the personal embodiment of the state; the nation’s arms are her arms, and there is no reason for a person to bear his or her own arms differenced.

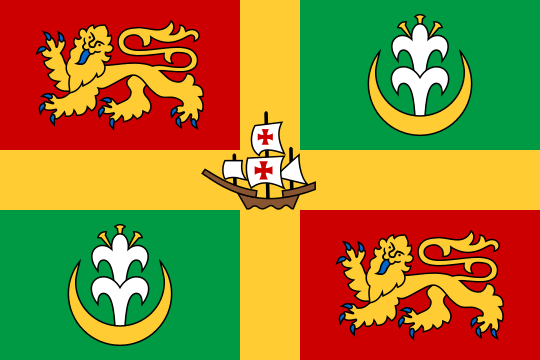

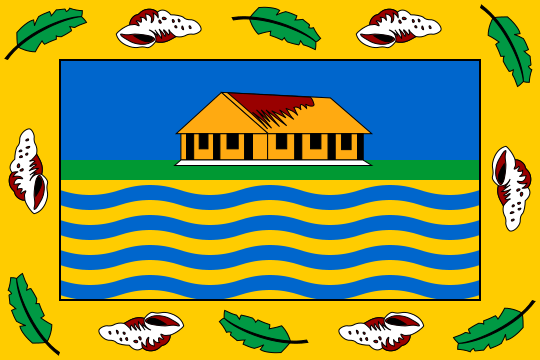

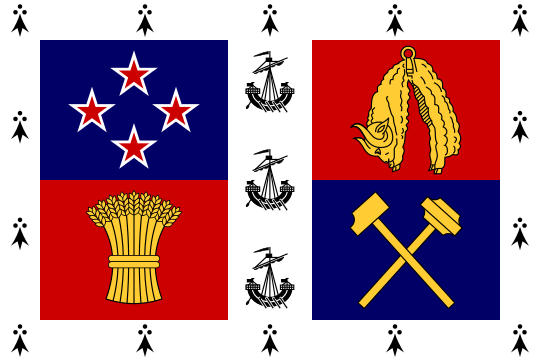

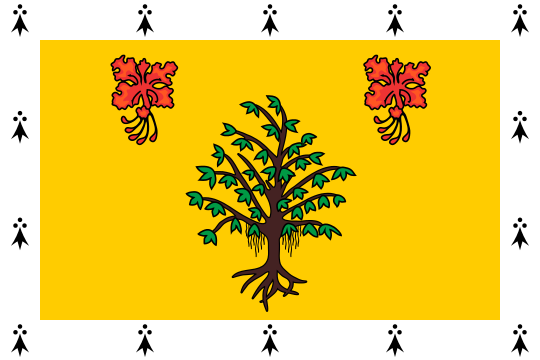

In accordance with heraldic custom, I suggest that in each realm she should use a banner of the national arms without defacement or difference – as illustrated by proposed standards for the Queen of Canada, the Queen of Grenada and the Queen of Tuvalu.

What of the Governors General? They do not represent the United Kingdom or the British government (this principle was first recognized in 1926), so there seems little justification for their flags bearing the crest of the British royal arms. Rather, since each Governor General is the personal representative of his or her own country’s queen, I propose that he or she should fly a differenced version of that country’s royal standard.

A bordure ermine for difference might be especially suitable; this has often been employed in heraldry as a mark of difference, and is used today in the United Kingdom by members of the royal family without banners of their own.

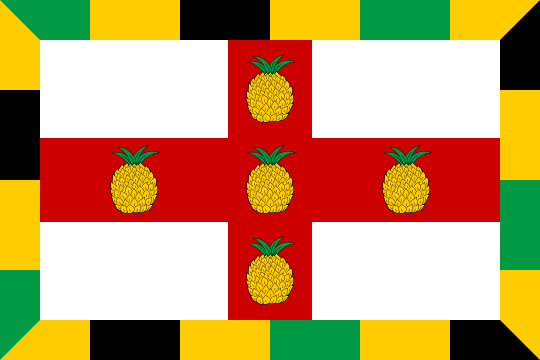

For the Governor General of Jamaica, ermine will not do, since the field of the Jamaican royal standard is already white. In this case, I suggest a bordure compony of the national colors of green, gold and black. Something similar could be done in the Bahamas, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, and St. Kitts and Nevis, where the same problem arises. Australia and Tuvalu present another problem: how should the vice-regal flag be differenced when the royal arms already have a bordure?

The overall result, in my view, is a series of flags which clearly denote each realm’s independence and distinct national identity, combining existing national symbolism and centuries-old heraldic principles to accurately reflect today’s constitutional realities.